Your Cheat Sheet for the Digital Services Act: What and for Whom

Cathleen Berger

If you search online for “Digital Services Act” (DSA) you get some 1.62 billion hits. Compared to only 513 million hits for its five years older “policy cousin”, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). All that, is of course a nerdy way of saying: the DSA is the EU’s latest regulation about to change the digital landscape, with effects beyond Europe. It will become fully applicable by February 2024.

It is also a 100-page document. And since not everyone enjoys such long reads, here it is in a nutshell: What will change and to whom does it apply?

What are digital services?

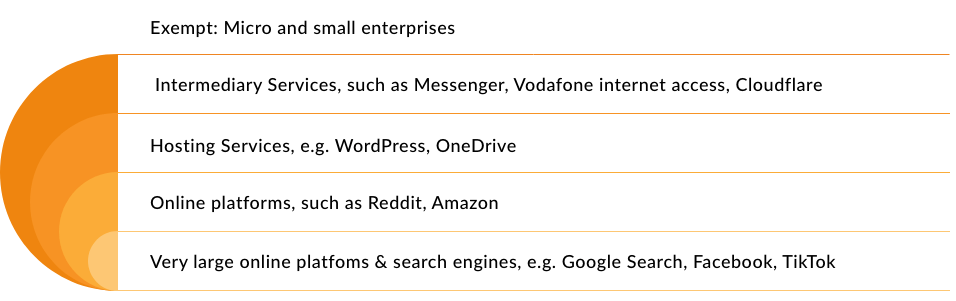

Digital services include things like social media, online marketplaces, your broadband provider, digital advertising and more. In more technical terms, the DSA applies to intermediary services that involve the transmission and storage of user-generated content.

However, thresholds and obligations differ depending on company size, turnover, and nature of the service. For instance, there are specific rules for hosting services and online platforms, as well as the adjacent category of “very large online search engines” (which I used to get 1.62 billion hits on the DSA).

Thresholds and obligations

Micro and small enterprises with fewer than 10 and 50 employees and an annual turnover below €2 and €10 million, respectively, are exempt. However, they do have to tackle illegal content as soon as they become aware of it. While things may change quickly in the realm of digital services, currently this would include platforms like Gettr, a microblogging site which is popular with the right-wing fringe scene.

In general, all providers are required to publish annual, machine-readable transparency reports outlining their content moderation measures, including policies, notices received, actions taken. Following size, the next threshold is about the kind of digital services provided namely whether it is a hosting service or an online platform.

Hosting services store content, while online platforms store and disseminate content to the public. In other words, Dropbox or your password manager: hosting service; Twitter or public Telegram groups: online platform.

Hosting services have limited liability, and most will only have to act once they become aware of illegal content. All must put notice and action mechanisms in place and notices must be addressed in a timely, non-arbitrary, objective manner – and should not solely rely on automated responses.

From a research and civil society perspective, obligations become more interesting for online platforms. In addition to the above, platforms must have a process in place that prioritises notices submitted by “trusted flaggers” – a status that is awarded to entities, not individuals, by national Digital Service Coordinators. Moreover, they are no longer allowed to profile their users for the sake of advertisements. And, in case the platform uses recommender systems to filter and target content based on an individual’s preferences, people must be able to choose and adjust such criteria.

Lastly, user numbers (measured in monthly active users) will determine the scope of additional obligations. All online platforms and search engines are required to publish their user numbers by February 17, 2023. Based on that, it will be decided which services are overseen by nationally appointed regulators, the so-called Digital Service Coordinator and which by the European Commission, namely the “very large” ones with over 45 million users (i.e., roughly 10% of the EU population). Note: This might also mean that one company can offer multiple services that fall within this scope (think Alphabet with Google and YouTube; Meta with Facebook and Instagram).

Transparency and accountability for very large services

No doubt, the obligations for very large online platforms (VLOPs) and very large online search engines (VLOSEs) have drawn a lot of scrutiny. The policymakers’ intention is very clear: increased consumer protection, transparency, and accountability. In that sense, the DSA aims to recognise that certain services have an outsized role and impact on public discourse. Critically, VLOPs are required to not only tackle criminal content but also content that poses societal risk, which is a far-reaching change in the efforts to counter disinformation, which may be misleading, manipulative, awful, or fabricated, yet is not always evidently illegal. The important element here is “risk”, which also points to monitoring developing dynamics and changing narratives, among others around fundamental rights, civic discourse, electoral processes, public security, gender-based violence, public health, pretection of minors, and people’s physical and mental well-being.

In short, very large services are expected to:

- Publish transparency reports every six months (instead of annually);

- Conduct annual risk assessments on the systemic risks of illegal content, such as potential negative effects on fundamental rights, elections, public security, or health;

- Establish an independent compliance function;

- Support annual external independent audits;

- Allow access to their data, including for real-time monitoring, for vetted researchers;

- Design at least one option of recommender systems not based on profiling;

- Pay an annual fee to cover the Commission’s cost of supervising their compliance.

Overall, when all is said and done, the DSA is about addressing power dynamics and the intend here is very clear: today, public discourse is largely happening on privately-managed platforms – which challenges democratic participation and oversight. Going forward, more transparency, insights, and options for compliance will exist that can help shift that balance if enforced well – or used strategically for advocacy, research, and policy development.

What’s next?

This overview necessarily leaves out a few interesting nuggets. In my next blog post, I will look more closely on the business side of things: what changes can we expect for very large online platforms and how much will it cost?