Disinformation – what it means and why we are dealing with it

Julia Tegeler

Democracies around the world are under pressure. Targeted disinformation campaigns run by anti-democratic forces are igniting and fueling polarization, radicalization and unrest among the population. Their goal: to destabilize democracies and expand their own influence. But what exactly is disinformation? Why is it so dangerous? And why have we committed to this topic in the context of our project Upgrade Democracy?

What is disinformation?

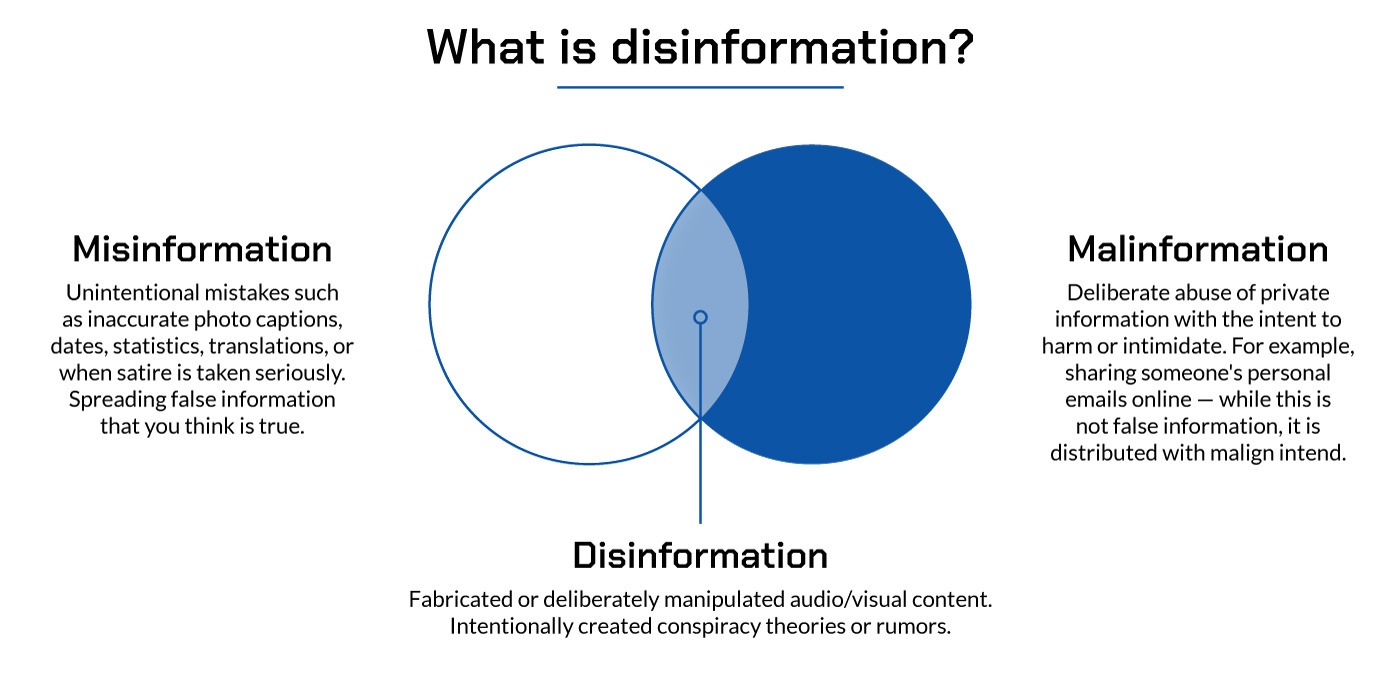

Disinformation is knowingly false or misleading information that is crafted and disseminated with the intention to deceive and manipulate. Those who spread disinformation usually want to influence social, political or economic processes to their own advantage. The intention to mislead is therefore an essential characteristic of disinformation. In contrast, when mistakes are made in reporting and false information or misleading content is disseminated unintentionally, we speak of misinformation. Unlike disinformation, misinformation is not usually disseminated systematically, making it easier to correct.

Likewise, to be distinguished from disinformation is malinformation. Malinformation describes information that is accurate but is published and disseminated with the intention of harming someone or stirring up polarization in society. Examples may include the publication of confidential information (leaks) or personal data with malicious intent against the individuals affected (doxing) as well as opinion mongering, certain forms of hate speech or even one-sided or incomplete reporting by tabloid media. The decisive factor in this context is the malicious intent.

Source: Council of Europe report (2017): INFORMATION DISORDER: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making

Source: Council of Europe report (2017): INFORMATION DISORDER: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making

What types of disinformation exist and how might they spread?

Disinformation can take various forms. Sometimes content is completely invented or fabricated, sometimes it is reproduced incompletely or removed from its original setting and placed in a different context. The crucial factor is the intent to deceive. Examples of disinformation are conspiracy narratives, or news reports that contain deliberately distorted information. Disinformation tends to be produced in the form of texts and fake or manipulated videos and photos (deepfakes). Because they (may) look deceptively real, it is increasingly difficult to identify and expose them as fakes. On the Internet and in social media, they then often spread quickly and uncontrollably. One of the reasons for this is that disinformation campaigns deliberately adopt the functional logic of social media platforms: The more emotionalised, controversial or exaggerated the statements are, the faster and farther posts and comments are spread by the algorithms of major social platforms, which are optimized for clicks and reactions. Increasing numbers of users and the trend toward more and more people informing themselves on social platforms reinforce the damaging potential of such campaigns. So, although they are not a new phenomenon, disinformation is taking on a new dimension and dynamic in our digitized public sphere.

Why is disinformation so dangerous?

The cornerstones of a vibrant and strong democracy include free access to information, a fact-based, fair debating environment and, associated with this, the opportunity to form independent, self-determined opinions. Disinformation directly undermines these pillars. It manipulates and distorts public discourse through false and misleading content, stirring fears and uncertainty as well as fostering disagreement and conflict among the population. In this way, disinformation can prevent citizens from forming their own opinions on the basis of facts and a fair discourse and thus discourage citizens from informedly participating in democratic processes, such as, elections, and from shaping politics in their own countries. In the long term, disinformation undermines trust in democratic institutions, processes and actors. That is why disinformation poses a major threat to democracy as a whole.

Why do we engage in the fight against disinformation?

We must consciously deal with the danger of disinformation and take measures to protect democratic, liberal processes. On the one hand, this involves taking targeted steps against the spread and influence of disinformation – for example, through the use of state regulation on platforms or by promoting media and information literacy. On the other hand, it is also involves strengthening a lively and diverse discourse culture against the backdrop of a digitised society and making democratic processes more sustainable for the digital future. In a nutshell: Democracy needs an upgrade. All of us – citizens, politicians, journalists, academics and activists – must ensure that democracy is equipped to meet the challenges of the digital public sphere and to make better use of the opportunities it contains. After all, digitisation not only provides anti-democratic forces with new means and channels for the spred of harmful disinformation campaigns. It also contains opportunity for democratic states and their citizens to create new possibilities for political participation, a more diverse discourse and greater transparency. Together and in constant exchange with experts and partners, we can and we want to contribute to this with our Upgrade Democracy project.

This is why we are committed to building bridges between a wide range of international actors working in this field. And also the reason for why we are disseminating solutions that successfully counter disinformation in their respective contexts, while making innovative use of digital tools to strengthen democracy. We are looking for good practices in several countries and on different continents.

Sources:

- German government: Clarification of terms: What is disinformation? (Bundesregierung: Begriffsklärung: Was ist Desinformation?)

- European Commission: Action Plan against Disinformation 2018 (Europäische Kommission: Aktionsplan gegen Desinformation 2018)

- Media Authority of North Rhine-Westphalia: Disinformation – Clarification of Terms Landesanstalt für Medien NRW: Desinformation – Begriffsklärung)

- The Media Authorities: Types of disinformation and misinformation (Die Medienanstalten: Typen von Desinformation und Misinformation)

- Heinrich Böll Foundation: Misinformation, disinformation, malinformation: Causes, developments and their influence on democracy. (Heinrich Böll Stiftung: Fehlinformationen, Desinformationen, Malinformationen: Ursachen, Entwicklungen und ihr Einfluss auf die Demokratie.)

- Council of Europe report (2017): INFORMATION DISORDER: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making