The utopia(s) of digital discourse spaces

Dr. Kai Unzicker

The digital public sphere was a promise. It was meant to bring about exchange, connection, and understanding. After more than two decades of social media and amid an AI hype, the initial optimism has given way to disappointment: Digital discourse spaces are now flooded with polarisation, hate, and misinformation. But what can we do to heal them? After two years of the Upgrade Democracy initiative, we present pathways towards healthier digital discourse spaces.

The initial hope was immense: Global connectivity and access to information promised a new era of reason and understanding. And indeed, digital communication has changed the world and repeatedly demonstrated its potential to fulfil these hopes. Would the Arab Spring, #MeToo, #MashaAmini, or FridaysForFuture have ever taken shape in this form without a global digital public sphere, with social media and messaging services? How quickly could we access the world’s knowledge without the hundreds of thousands of volunteers who contribute to Wikipedia daily—free, multilingual, and in constant critical reflection? How many exams or DIY repairs would fail without support from countless YouTube videos? Undoubtedly, the digitised world has its bright side.

While the 20th century was marked by mass societies, where mass media (few-to-many) wielded great political influence, the 21st century has ushered in an era of individualised, decentralised online communication, where anyone can be both a sender and a receiver (many-to-many). This radical democratisation of the public sphere has made previously marginalised groups more visible and empowered. Yet, it has also led to a radicalisation of democratic discourse. When everyone has a voice and amplifiers, it rarely results in harmonious choir; more often, it is a cacophony of different tunes and tones. The immediacy of social media communication encourages emotions and distortions, which gain far more traction than in traditional, editorially curated media.

Digital communication and the digital public sphere, especially as embodied by profit-driven social media platforms operating on the logic of the attention economy, increasingly appear dysfunctional and even threatening to democracy. But must this be the case? What might a realistic vision of a functional digital public sphere look like—one that connects people, fosters constructive discourse, and promotes understanding rather than division? Clearly, this cannot be about realising the utopia of a rational, power-free, and civilised digital discourse. The past two decades have shown how challenging that is. However, what would be a desirable improvement over the current state, achievable with the actual actors involved (companies, political institutions, users)? A thorough problem analysis is necessary to identify which steps can bring about this improvement.

The players – An information ecosystem out of balance

It would be too simplistic to blame the woes of digital discourse on any single actor. Neither Big Tech’s profit-driven operation of communication platforms nor political institutions’ struggle to regulate the so-called “new territory” are solely at fault. Nor can authoritarian regimes or extremists, domestic or foreign, be held solely responsible for the state of digital discourse. It is also not just down to human psychology, which might inevitably lead to the worst forms of online interaction.

In fact, it is the toxic interplay of all these actors, with their intentions, actions, reflexes, and mechanisms, that creates the current situation. The information ecosystem—comprising all the parts that can only exist together, and which form the public discourse space—is out of balance. For tech companies, the time users spend on their platforms equates to money. Therefore, they have optimised their algorithms to maximise this time. Newsfeeds are filled with one post after another, new content is suggested based on preferences, and the promise is that with every swipe or click, better entertainment, bigger surprises, fresher news, or more outrageous scandals await. It is like sugary treats or fatty crisps: Once you start, it’s hard to stop. But here, it is emotions at play, not sugar or fat. Anything that stirs emotions works. While this mechanism is already problematic, it would be less worrying if it were only about fun, entertainment, or sex. But – and here we encounter the unscrupulous and often malicious actors who have quickly grasped and exploited the mechanism – fear, anger, envy, and greed work even better as fuel on social media.

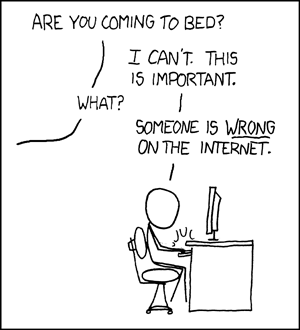

“Someone is wrong on the internet” or 90, 9, 1

Under these conditions, constructive debate, civilised exchange, or understanding is hard to achieve. However, it is an illusion to believe that digital discourse represents the entirety of public opinion. For a while, there was a tendency to read general sentiment from Twitter’s (now X) trending topics or individual posts. Yet, the commonly cited 90, 9, 1 rule from online communities likely holds truer. While everyone can potentially participate in the digital public sphere, few do. The rule of thumb is that 90 per cent of users are passive. Around 9 per cent engage by commenting or using standardised forms of engagement like likes or shares. However, actual content creation is done by just a tiny fraction, roughly 1 per cent of users. These individuals often hold strong views. A famous XKCD meme illustrates this well: The 1 per cent of content creators and the 9 per cent who interact often do so either out of strong agreement or—perhaps more frequently—vehement disagreement. The meme shows a stick figure refusing to go to bed because, as it says, “Someone is wrong on the internet.”

This dynamic causes discussions on social media or in news site comment sections to be more polarising and conflict-driven, rather than constructive through the exchange of arguments. Articles, posts, videos, and comments that provoke strong emotional reactions get the most attention. As a result, online debates appear more polarised, conflict-ridden, and emotional than their real-world, face-to-face counterparts.

Less reporting, more opinion

In this environment, whether you are a private user, professional content creator, or media company, gaining reach means focusing on sensationalism, emotional appeal, and controversial opinions. The potential for comprehensive, transparent information and background quickly gives way to a reality dominated by strong opinions and interpretations. The distinction between fact and opinion often gets lost. Calls for “freedom of speech” often merely mean claiming the right to assert anything without challenge, whether it is that bleach can cure Covid, that economic elites are replacing populations, or that climate change is a lie.

Is news consumption divided?

The trend towards emotionally charged and opinionated content has not spared editorial media. Traditionally, journalism’s role—with its standards and ethics—has been to select what matters from the endless stream of reportable events. This has always included the interpretation of the world’s state through commentary and opinion pieces. But as newsrooms and publishers come under increasing pressure, they are tempted to follow the logic of the attention economy. Clickbait, emotionalisation, and increasing polarisation are the result. While these phenomena aren’t new to journalism (think “tabloids”), they continue to spread. Where successful, quality journalism—now reliant on solid financial backing—ends up behind paywalls. This threatens to further divide those who can afford curated news from those who rely on snippets and dubious websites. Some national or international quality outlets may still find sustainable business models and interested consumers in the future, but whether this will work for local and regional media remains uncertain.

The next step: AI-generated and personalised

While news media are still searching for ways to monetise their online content, tech companies are one step ahead. Rather than offering reach to journalistic content, they play with ways to distribute news content directly. AI can provide users with personalised news—based on interests, location, or time of day—straight into their timeline or search results. Where the information comes from, whether it was researched by journalists, and whether your neighbour is receiving the same news or spin is becoming increasingly difficult to determine. What is more, the social aspect of social media is gradually disappearing. It is no longer your network shaping your worldview, but rather a smaller number of tech gatekeepers delivering the news, driven perhaps less by societal value and more by commercial potential. This presents another serious threat to the state of public discourse.

How to ease the digital discourse space

That said, it is not as if nothing can be done. The current state of the digital public sphere is the result of a complex interplay of various actors, and there is room for change. A key step is to hold platform operators—who dominate these digital spaces—more accountable. Platforms must be regulated, and the rules under which they employ algorithms must be made transparent and verifiable. The European Digital Services Act provides some initial tools for this. But this alone won’t suffice. Further political measures are needed to curb the influence of disinformation, targeted polarisation, and malicious actors. This could be achieved through supporting independent fact-checkers and promoting media literacy in educational institutions.

Media organisations themselves must also take responsibility. This means adhering to their ethical standards and resisting the temptations of attention-driven economics. Journalistic quality must not be sacrificed for quick clicks. Ultimately, users themselves must take responsibility, critically questioning the content they consume and how they contribute to the quality of discourse.

While these measures aren’t exhaustive, they represent important steps towards stabilising the digital discourse space. Achieving this will require collaboration between politics, corporate sector, and civil society. Only by working together can we turn the digital space into a place for exchange, understanding, and democratic participation. One thing is clear: Democracy needs a public sphere where critical discourse and political debate are possible. It will, however, collapse if that space is flooded with hate, conspiracy theories, and deliberate manipulation.

Further reading and exploration

- Digital Turbulence: Challenges facing Democracies in Times of Digital Turmoil

- Social Media and Democracy. The State of the Field and Prospect for Reform

- Truth Decay and National Security. Intersections, Insights, and Questions for Future Research

- Generative Artificial Intelligence and Political Will-Formation

- Digital Discourses and the Democratic Public Sphere 2035